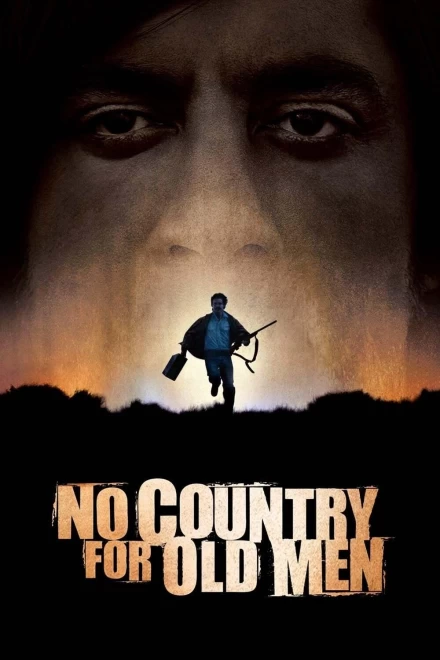

Directed by: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Starring: Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, Tommy Lee Jones

Genres: Crime, Psychological Thriller, Neo-Western

🧠 Introduction – A Film Built on Unanswered Questions

No Country for Old Men is a film that actively resists explanation. Rather than resolving its central conflicts, it removes them abruptly, leaving viewers with absence instead of closure. The Coen brothers adapt Cormac McCarthy’s novel with remarkable restraint, preserving its philosophical ambiguity. The result is a film that feels less like a conventional crime thriller and more like a meditation on violence, chance, and moral exhaustion.

Over the years, the film has inspired intense debate. Viewers argue not only about what happens, but about what the film means to say about fate, evil, masculinity, and the passing of time. Is Anton Chigurh a symbol rather than a man? Does Llewelyn Moss die because of fate or choice? Is Sheriff Bell the true protagonist? The film never confirms or denies these interpretations. Instead, it invites them.

🪙 Theory 1 – Anton Chigurh as Fate Incarnate

One of the most enduring fan theories suggests that Anton Chigurh is not merely a hitman, but a physical embodiment of fate. His rigid moral logic, emotionless demeanor, and obsession with chance align him more with a force of nature than a human antagonist. Chigurh does not see himself as choosing who lives or dies. He frames his actions as the inevitable outcome of prior decisions made by others.

The coin toss is central to this interpretation. When Chigurh asks his victims to call it, he removes personal responsibility from himself. The outcome, he implies, was decided long before the coin was flipped. This ritual transforms murder into inevitability. Fans who support this theory argue that Chigurh’s survival throughout the film reinforces the idea that fate cannot be stopped, only endured.

Critics of this theory point out that Chigurh selectively applies his rules. He kills some people without offering a choice and spares others arbitrarily. This inconsistency suggests that Chigurh is not fate itself, but a man who uses the language of fate to justify his violence.

🎭 Theory 2 – Anton Chigurh as a Delusional Moral Absolutist

A competing interpretation argues that Chigurh is not symbolic, but deeply human. According to this theory, his philosophy is a coping mechanism designed to absolve himself of guilt. By framing his actions as dictated by chance or principle, he avoids confronting the reality that he chooses violence.

Supporters of this view point to moments where Chigurh’s composure cracks. His reaction to Carla Jean’s refusal to call the coin reveals frustration. When the ritual fails, Chigurh becomes visibly unsettled. This suggests that his belief system depends on others participating in it. Without that participation, his authority collapses.

From this perspective, Chigurh represents ideological extremism. He is dangerous not because he is supernatural, but because he believes absolutely in a self constructed moral code that cannot be questioned.

🔫 Theory 3 – Llewelyn Moss Dies Because He Breaks the Code

Many viewers debate whether Llewelyn Moss’s death is the result of bad luck or moral failure. One theory argues that Moss dies because he repeatedly violates the unspoken rules of the film’s world. He takes the money knowing it is dangerous, returns to the scene out of guilt, and consistently underestimates the forces pursuing him.

His decision to go back with water for the dying man is often cited as the turning point. It is a humane act, but one that exposes him. In a world governed by brutal efficiency, compassion becomes a liability. This interpretation frames Moss as a tragic figure whose decency is incompatible with the violent reality he enters.

Opposing this view, some argue that Moss is punished not for moral failure, but for refusing to submit to fate. He believes he can outsmart the system. His death reinforces the film’s bleak assertion that intelligence and skill offer no protection against chaos.

🚪 Theory 4 – The Meaning of Llewelyn’s Off-Screen Death

One of the most controversial choices in the film is the decision to kill Llewelyn Moss off-screen. Fans have long debated why the Coens deny the audience this confrontation. One interpretation suggests that this choice reflects the randomness of violence. Important lives end without ceremony, spectacle, or narrative payoff.

Another theory argues that Moss’s death is deliberately unimportant to the film’s central message. The story is not about the chase or the money. It is about the world that produces such violence. By removing Moss abruptly, the film shifts focus to Sheriff Bell, whose inability to understand or stop what is happening becomes the emotional core.

This narrative disruption forces the audience into Bell’s perspective. Like him, we arrive too late and are left with only aftermath.

🧓 Theory 5 – Sheriff Bell as the True Protagonist

Many fans argue that Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, not Llewelyn Moss, is the film’s true protagonist. Moss represents the illusion of agency, while Bell represents reflection. Bell does not drive the plot forward. He reacts to it, slowly realizing that the world has moved beyond his understanding.

Bell’s monologues about the past reveal a deep sense of moral exhaustion. He believes violence has escalated beyond anything he can comprehend, yet the film subtly suggests that brutality has always existed. What has changed is Bell’s capacity to face it.

Under this interpretation, the film is not about crime, but about aging and displacement. Bell is a man whose ethical framework no longer aligns with reality. His retirement is not cowardice, but surrender to inevitability.

🌙 Theory 6 – The Final Dream Explained

The film ends with Bell recounting two dreams about his father. The second dream, in which his father rides ahead carrying fire, has generated countless interpretations. One popular theory suggests the fire represents moral order or meaning. Bell’s father carries it forward into the darkness, suggesting continuity beyond Bell’s lifetime.

Others interpret the dream as Bell’s acceptance of death. His father waiting ahead implies that Bell’s journey is nearing its end. The fire offers comfort, not hope of change. The world will not be fixed, but Bell will not face the darkness alone.

Crucially, the film cuts to black without commentary. The dream does not resolve anything. It merely reframes Bell’s relationship to uncertainty.

🎯 What the Film Refuses to Answer

No Country for Old Men deliberately avoids moral resolution. It never tells the audience whether evil is new or eternal, whether fate is real or constructed, or whether violence has meaning. Each theory remains plausible because the film is designed as a philosophical mirror rather than a narrative puzzle.

The debates surrounding the film persist because it reflects different anxieties depending on who watches it. Some see inevitability. Others see moral collapse. Some see divine indifference. Others see human failure. The film accommodates all of these readings without committing to any of them.

🏁 Final Thoughts – A Film That Lives in Debate

No Country for Old Men endures because it refuses to explain itself. Its power lies in what it withholds. By denying catharsis, the film forces viewers to sit with discomfort, uncertainty, and reflection. Each theory reveals more about the viewer than the film.

Rather than offering answers, the Coen brothers present a world where meaning is unstable and violence resists narrative order. The debates are not a byproduct of the film. They are its purpose. In that sense, No Country for Old Men is not a story to be solved, but a question that continues to echo long after the final frame.