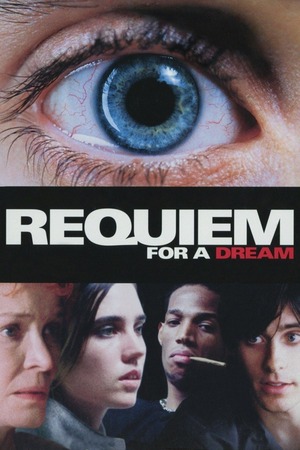

Director: Darren Aronofsky

Starring: Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Marlon Wayans

💊 Introduction: A Descent in Four Movements

Requiem for a Dream is not merely a film about drug addiction—it is an operatic tragedy split into seasonal acts, where hope is ritualized, dreams are corrupted, and reality collapses in slow motion. Darren Aronofsky’s 2000 adaptation of Hubert Selby Jr.’s novel unfolds like a fever dream, where repetition, stylized editing, and claustrophobic close-ups create a symbolic universe. Four characters—Harry, Marion, Tyrone, and Sara—descend together, each chasing a distinct illusion of happiness. Their downfall, devastating in its symmetry, serves as a requiem not only for lost dreams, but for the very notion of selfhood.

What makes Requiem remarkable is not just its relentless pacing or disturbing imagery, but the rich symbolic fabric that weaves psychological despair with sociocultural critique. This is a film saturated with metaphors, from food and television to color palettes and visual repetitions—each thread drawing us deeper into the abyss of broken desires.

📺 The Television as Delusion: Sara Goldfarb's Obsession

Sara Goldfarb, portrayed with painful precision by Ellen Burstyn, is perhaps the most tragic figure in the film. Her addiction is not to street drugs, but to television, to appearances, to validation. Her recurring vision—appearing on a self-help show in a red dress—epitomizes the American dream distorted by consumer culture. She pops amphetamines not for pleasure, but to fit into a dress that symbolizes belonging, visibility, and love.

The TV becomes an omnipresent symbol of illusion. Its garish colors and plastic smiles infiltrate Sara’s hallucinations, ultimately consuming her mind. Her descent into madness culminates in scenes where the boundary between the TV and her living room dissolves completely—a metaphor for the way media can displace reality. Sara’s journey critiques how modern culture equates self-worth with external perception, and how women, especially aging ones, are reduced to their appearance in public space.

🪞Mirrors, Fragmentation, and the Shattered Self

The mirror motif recurs across all character arcs. Each individual in the film is in a state of dissociation—unable to reconcile their dream-self with their actual condition. Sara stares into her TV’s reflection, not to see herself, but to see who she could be. Harry and Marion’s apartment is cluttered with reflective surfaces, suggesting a fractured intimacy. Tyrone’s nostalgia for his childhood—visualized through flashbacks—serves as a kind of inner mirror, one filled with longing and unresolved trauma.

These mirror scenes highlight a Jungian fracture in the psyche. Aronofsky uses repetition of sound and image to heighten this dissociative experience—rapid eye dilation, pill-popping, and syringe plunges become hypnotic rituals, symbolizing the addictive loop not just of drugs, but of emotional avoidance. Reality fragments into ritual, and identity into scattered reflection.

🎨 Color Symbolism: A Gradual Corruption

The seasonal structure—summer, fall, winter—parallels a visual descent into darkness. Early scenes are bathed in warm, bright hues, often highlighting a seductive hope. As the story progresses, colors drain, shadows intensify, and the frame becomes claustrophobic. This chromatic journey mirrors the arc of each character’s internal collapse.

Sara’s scenes are tinged with sickly yellows and television blues, evoking a synthetic warmth that grows increasingly hallucinatory. Harry and Marion’s palette shifts from sunlight to gray as their relationship becomes transactional and desperate. Tyrone’s trajectory follows colder, more impersonal tones—his story, entwined with racial memory and abandonment, fades into institutional sterility.

⚖️ Addiction as Metaphor: More Than Drugs

While heroin and pills are literal devices in the story, they serve as metaphors for larger addictions: validation, love, control, safety. Sara’s pills are no less dangerous than Harry’s needle. Marion’s descent into sex work is not a result of drug addiction alone, but of emotional dependency and creative despair. Tyrone’s spiral is linked to a loss of purpose, a search for maternal affection in an unforgiving world.

Addiction here becomes a stand-in for existential terror. Aronofsky shows us that addiction is not merely a chemical problem—it is a spiritual void. The characters are not chasing highs; they are running from stillness, from themselves, from the silence of unmet need. The “repetition montage” style—fast cuts of drug intake rituals—echoes the compulsive nature of avoiding reality.

🛏️ Isolation and Institutionalization

All four characters end up in some form of institutional space—prison, psychiatric ward, hospital bed. These sterile, impersonal locations signify the end of the self. The characters have chased fantasy to the point where they are no longer agents of their own lives. In the final montage, all four lie in fetal position, facing the void. This identical ending shot underscores the film’s thesis: that the pursuit of illusion, in any form, leads not to transcendence, but obliteration.

The fetal position is not a rebirth—it is regression. The “requiem” of the title is not just for the characters, but for hope itself. Aronofsky suggests that in a world where connection is hollow and fantasy is marketed as salvation, the only logical outcome is disintegration.

🧠 Psychological Collapse as Cinematic Form

The visual language of the film is deliberately manic and overwhelming. Aronofsky’s use of split screens, extreme close-ups, and repetition creates an immersive psychological texture. We are not observers—we are participants in the characters’ collapse. This is not aesthetic for its own sake; it mirrors the way mental illness distorts time, space, and perception.

As the film progresses, the boundaries between interior and exterior collapse. Sara’s hallucinations bleed into her kitchen. Harry’s arm becomes a grotesque symbol of decay. Marion loses all control over her body and boundaries. Cinematic form becomes a vessel for inner chaos, and the audience, trapped in its rhythm, is denied the safety of emotional distance.

🎯 Final Thoughts

Requiem for a Dream is a visual eulogy—not only for its characters, but for a society that promises transcendence and delivers isolation. Its symbolism is dense, often overwhelming, but always purposeful. Aronofsky does not offer catharsis or redemption. Instead, he offers a mirror—one that shows how dreams, when twisted by fantasy and commodification, become nightmares.

This is not a cautionary tale about drugs. It is a requiem for all the illusions we cradle to avoid being alone with ourselves. And in that, it remains one of the most harrowing and symbolic cinematic explorations of the human condition.