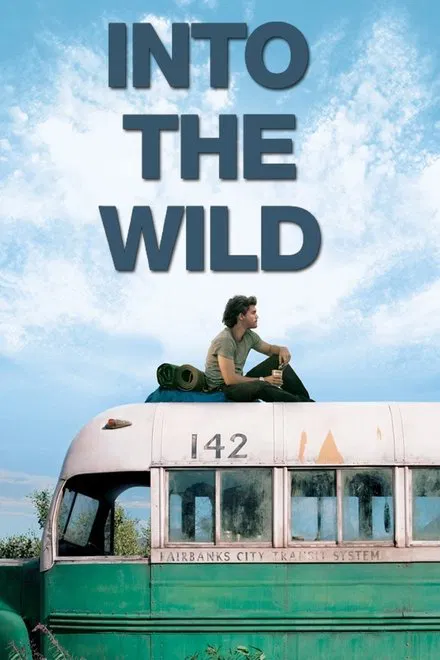

Directed by: Sean Penn

Starring: Emile Hirsch, Marcia Gay Harden, William Hurt, Jena Malone, Catherine Keener, Hal Holbrook

🌲 Introduction: A True Story of Escape

Into the Wild (2007), directed by Sean Penn and adapted from Jon Krakauer’s acclaimed non-fiction book, chronicles the journey of Christopher McCandless—a young man who abandons his privileged life for a radical quest into the American wilderness. The film is part adventure, part elegy, and part critique: a story of idealism, solitude, and the yearning for transcendence. McCandless’s odyssey, both exhilarating and tragic, has inspired debate over the meaning of freedom, the dangers of purity, and the complexities of living “authentically.”

🧭 The Pursuit of Radical Freedom

McCandless, played with fierce vulnerability by Emile Hirsch, rejects materialism and social expectation after college graduation, giving away his savings and setting out under the name “Alexander Supertramp.” His journey takes him across the American West, through the deserts of Arizona, the wheat fields of South Dakota, and ultimately to the remote wilds of Alaska.

The film frames this quest as both spiritual and political. Chris seeks freedom not just from society, but from family pain and personal trauma. His encounters with a diverse cast of wanderers and outsiders—Jan and Rainey, Wayne Westerberg, and the elderly Ron Franz—illuminate the beauty and peril of isolation. Each friendship shapes Chris’s understanding of connection and loneliness, yet he remains determined to live “raw,” untouched by compromise.

🌌 Nature, Transcendence, and the Limits of Self-Reliance

Penn’s cinematography romanticizes the grandeur of the wild: rivers, mountains, and endless sky. The natural world becomes a character—both sanctuary and adversary. For Chris, nature is the crucible in which meaning and purity are forged. He finds joy in survival, contemplation, and self-invention. The “Magic Bus,” abandoned in the Alaskan backcountry, becomes his hermitage and, ultimately, his tomb.

Yet the wild is indifferent to idealism. The turning point arrives when Chris, weakened by starvation and poisoned by wild potato seeds, confronts the reality that freedom without relationship is incomplete. The message he scrawls in his final days—“Happiness only real when shared”—is both epiphany and regret.

🪞 Family, Forgiveness, and Ambiguous Legacy

Interwoven with Chris’s journey are flashbacks to his family: loving, dysfunctional, unable to bridge the gap between their world and his. The film resists easy blame, depicting Chris’s parents as flawed but human. The pain of unspoken words and unresolved conflict haunts both Chris and those he leaves behind. His odyssey is, in part, an attempt to escape their shadow—and a testament to the impossibility of total escape.

“Into the Wild” refuses to romanticize its subject or condemn him. Chris’s death is neither meaningless nor heroic, but a tragic consequence of radical choices. The film’s power lies in its refusal to resolve the tension between the necessity of society and the allure of solitude.

🎯 Final Thoughts: Lessons from the Wild

Into the Wild endures because it raises timeless questions: What is the cost of living authentically? Where is the boundary between courage and recklessness, purity and pride? Chris McCandless’s story offers no simple answers, only a haunting invitation to reexamine our own lives—for, as he writes, “the core of man’s spirit comes from new experiences.” In its bittersweet beauty, the film leaves us not with judgment, but with wonder and humility before the wild inside and out.